In this Part 2 of a series I again delve into some technical detail, but this time in an effort to catch a little bit of the form and movement, the dynamism, of genetic and epigenetic processes. I well realize that the material in this series will present a challenge to many readers. The presentation is both denser and lengthier than normal for NetFuture. I've been motivated to produce these articles by the awareness that epochal changes in biology are underway, and that the popular media have so far grossly failed to give the public any realistic feel for what is happening. A reasonably detailed and generally accessible summary of the ongoing, highly technical research needs to be available somewhere.

The readership for such material may be rather more limited than for the general run of NetFutures, but I consider this readership extremely important. And you can help me out in one regard: if you find these articles of use, please drop me a line to let me know. I will also welcome any suggestions for improvement.

I am currently expecting that there will be a total of four articles tracing some of the current research relating to epigenetics and gene regulation. These will be followed by attempts to draw out the significance of the work for biology, for science in general, and for the controversial notion of "holism". I do believe we are headed toward a revision of the scientific outlook that may be the equal of any of the great "paradigm shifts" of the past — this despite the fact that penetrating discussion of the implications of the current work has scarcely even begun. It's almost as if no one — or, at least, no one who is attempting to publish in the primary, peer-reviewed journals — has quite dared as yet to step outside the old rhetoric of "genetic code", "mechanism", "building blocks", and all the rest, and actually face what is going on.

On a different note: if you are interested in evolution, you might want to check out two articles in the latest issue of The Nature Institute's hardcopy newsletter, In Context. These articles have been posted to the web.

SLT

(You will find the latest versions of the currently available parts of this series at the website, "From Mechanism to a Science of Qualities".)

By clicking on the shaded rectangles at the end of many scientific terms, you can immediately read a definition of the terms in a separate window. This requires JavaScript to be enabled in your browser.

The decades following the 1953 discovery of the double helix![]() were a time

when everything important seemed to hinge on the fixed and definitive

"genetic code"

were a time

when everything important seemed to hinge on the fixed and definitive

"genetic code"![]() . The

researcher's task was to work out explicitly a prescriptive logic already

contained in the code. It was not a time when molecular biologists were

likely to preface their discussions of gene expression

. The

researcher's task was to work out explicitly a prescriptive logic already

contained in the code. It was not a time when molecular biologists were

likely to preface their discussions of gene expression![]() with

statements like this:

with

statements like this:

DNA is a living molecule, writhing, twisting and bending in response to the physical forces applied to it by genetic processes (Kouzine et al. 2007).Nor was it a time when gene packaging materials and a diverse bestiary of regulatory factors

Or, again, as recently as 1996, when the yeast genome was fully decoded and all its secrets supposedly laid bare, who would have expected to read this a decade further on:

Even for a [yeast] genome that has been studied intensively since it was sequenced10 years ago, a glimpse into the complexity of its transcriptional

architecture makes this genome appear like novel territory (Lior 2006 et al.).

How could the relatively simple yeast genome remain novel ten years after the complete unveiling of its structural sequence? And as for the choreography of the cellular "dance", isn't this a mere metaphor? Surely the authors quoted above did not really mean to say that a dance controls the genome! After all, the decisive logic of the genomic code is supposed to be what ultimately controls everything else.

Or so it has been thought. But the pace of discovery today is almost blinding, and it seems to be a time for the loosening of old thought patterns. The appeals to genomic plasticity, balance, tension, and context, the language of dynamism and artistic movement — these are not mere signs of a collective weakness for poetic invention, but rather are evoked by the phenomena under consideration. There is, in fact, nothing to prevent the contemporary molecular biologist from thinking along the following lines:

The organism must be rooted in something more than an abstract, fixed, and unchanging logic. It is a dynamic material presence, and requires a materially effective genesis. If DNAand all the other contents of the living cell provide the physical foundation for the organism as a whole — for the seeing eye, the beating heart, the graceful and compelling movement of the ballet dancer — then why shouldn't their own, molecular performance be at least as artful and complex as that which they support on a larger scale? Why shouldn't their gestures be as meaningful and expressive as those of the organs whose development they so effectively underwrite? Is there any reason to think that the life animating the cell and its DNA should be any more reducible to a static logical sequence — should be any less subtle or capable or dynamic — than eye, heart, and ballerina? Why should we project tiny, neatly programmed mechanisms into the cell when the organisms we see don ’t at all look or behave like such mechanisms?

Of course, these thoughts, especially if expressed in this way, would still today appear rather eccentric. There are, as we will see, logic-centered and mechanistic habits of thought that fiercely oppose giving embodied (and therefore observably aesthetic) form and movement their due.

But nevertheless, the landscape on which we all must move with our ideas,

outworn or forward-looking as they may be, is inexorably changing. It's a

landscape upon which, less than a decade after the height of the fever

induced by the Human Genome Project, the author of a review in a major

biological journal could write that genome![]() mappings and

genomic comparisons of species "shed little light onto the Holy Grail of

genome biology, namely the question of how genomes actually work" in

living organisms (Misteli 2007).

mappings and

genomic comparisons of species "shed little light onto the Holy Grail of

genome biology, namely the question of how genomes actually work" in

living organisms (Misteli 2007).

And so today whoever would take a researcher to task for eccentric thinking might have a harder time of it than usual. In surveying contemporary molecular biology, the least anyone can say is, "Things are getting very interesting!"

If you arranged the DNA![]() in a human

cell linearly, it would extend for about two meters. How do you pack all

that DNA into a cell nucleus about ten millionths of a meter in diameter?

According to the usual comparison it's as if you had to pack 24 miles (40

km) of extremely thin thread into a tennis ball. Moreover, this thread is

divided into 46 pieces (individual chromosomes

in a human

cell linearly, it would extend for about two meters. How do you pack all

that DNA into a cell nucleus about ten millionths of a meter in diameter?

According to the usual comparison it's as if you had to pack 24 miles (40

km) of extremely thin thread into a tennis ball. Moreover, this thread is

divided into 46 pieces (individual chromosomes![]() ) averaging,

in our tennis-ball analogy, over half a mile long. Can it be at all

possible not only to pack these into the ball, but also to keep them from

becoming hopelessly entangled?

) averaging,

in our tennis-ball analogy, over half a mile long. Can it be at all

possible not only to pack these into the ball, but also to keep them from

becoming hopelessly entangled?

Let's begin visualizing the situation in a little more detail.

Imagine you have a rope consisting of two strands spiraling around each

other in the manner of a double helix![]() . Imagine

further that there are short, fairly rigid rods connecting the two strands

at regular intervals along their entire length. There are many of these

rods — roughly ten along the brief length required for one strand to

spiral completely around the other a single time. Each rod represents two

linked nucleotide bases

. Imagine

further that there are short, fairly rigid rods connecting the two strands

at regular intervals along their entire length. There are many of these

rods — roughly ten along the brief length required for one strand to

spiral completely around the other a single time. Each rod represents two

linked nucleotide bases![]() , or base

pairs

, or base

pairs![]() (complementary "letters" of the genetic code

(complementary "letters" of the genetic code![]() ), with one

base bound tightly to one strand of the rope and the other bound to the

complementary strand.

), with one

base bound tightly to one strand of the rope and the other bound to the

complementary strand.

It would be good if the rope, in its double helical form, has been soaked

in a starch solution or some other stiffening agent. This is because DNA,

as a result of its chemical constitution, possesses a degree of natural

rigidity; left to itself, the overall structure resists bending, and one

strand "wants" to wrap around the other a fixed number of times for any

given length of the helical axis![]() . It is

possible to increase this number somewhat (that is, to wind the strands

more tightly around each other) or else to decrease it (unwind the

strands). But in both cases this is to work against the stiffness of the

natural structure, and therefore to create tension that must be

accommodated in one way or another.

. It is

possible to increase this number somewhat (that is, to wind the strands

more tightly around each other) or else to decrease it (unwind the

strands). But in both cases this is to work against the stiffness of the

natural structure, and therefore to create tension that must be

accommodated in one way or another.

You have doubtless seen this accommodation many times. Hold the ends of a

two-stranded rope in your hands and begin to twist one of the ends so as

to tighten the spiraling strands. Before long you will find the rope

coiling into something like a figure eight, and then into ever more

complex forms as you continue twisting, until finally you end up with a

"nest of worms". And much the same happens if you twist in the opposite

direction, as if you were trying to unwind or loosen the spiraling

strands. The coil resulting from a tightening twist is called a positive

supercoil![]() , while a

loosening twist produces a negative supercoil1.

, while a

loosening twist produces a negative supercoil1.

The forces involved in these deformations can be very large — as you

will have discovered if you have ever tried to coerce a stiff rope through

multiple stages of coiling by twisting its ends, or even if you have found

yourself wrestling with a recalcitrant garden hose while trying to coil it

neatly. Matter can be very resistant! Analogous forces come into play

with chromosomes![]() as well.

as well.

DNA![]() is often in

a negatively supercoiled state to one degree or another — and, as we

will soon see, this is owing to additional reasons beyond the fact that,

in order to fit into its own space in the nucleus, it is coiled, bent,

wound and otherwise structured to an almost unfathomable degree. The

question is how any sort of order is maintained: how is the nest of worms

packaged and managed in every cell of the human body in a manner allowing

the thousands of distinct, individual genes, and perhaps hundreds of

thousands of regulatory sequences

is often in

a negatively supercoiled state to one degree or another — and, as we

will soon see, this is owing to additional reasons beyond the fact that,

in order to fit into its own space in the nucleus, it is coiled, bent,

wound and otherwise structured to an almost unfathomable degree. The

question is how any sort of order is maintained: how is the nest of worms

packaged and managed in every cell of the human body in a manner allowing

the thousands of distinct, individual genes, and perhaps hundreds of

thousands of regulatory sequences![]() , to come to

harmonious expression within the complex life of the larger cell?

, to come to

harmonious expression within the complex life of the larger cell?

The first step in DNA packaging involves tiny "spools" made of histone![]() proteins

— some thirty million of them in the human genome

proteins

— some thirty million of them in the human genome![]() , so that

there can be several hundred thousand or more in a single chromosome

, so that

there can be several hundred thousand or more in a single chromosome![]() . The DNA

double helix

. The DNA

double helix![]() commonly

wraps about two times around this spool, continues on for a short

distance, then wraps around a second spool, and so on. The DNA-enwrapped

spool is called a nucleosome

commonly

wraps about two times around this spool, continues on for a short

distance, then wraps around a second spool, and so on. The DNA-enwrapped

spool is called a nucleosome![]() .

.

This first level of DNA packaging is often described as "beads on a

string". (See third image from left in the figure below.) The DNA and

histone spools, together with numerous other attached proteins and smaller

chemical groups, give an overall, ever-changing form and structure to what

is called chromatin![]() — the

actual material of the chromosome. But with this spooling of the double

helix we have seen only the beginning of the compaction that must occur in

order to fit the chromosome into the cell nucleus. Unfortunately, the

higher-order structures of the compacted chromosome are still little

understood. The spools with their DNA somehow get packed into dense,

three-dimensional arrangements, and this entire arrangement coils further

upon itself beyond anyone's current ability to unravel the details. Such

difficulty, however, rarely hinders the adventurous from offering visual

models. So, for what it is worth, here is a conventional picture showing

several stages in the condensation of a chromosome (it is best viewed at

full screen width):

— the

actual material of the chromosome. But with this spooling of the double

helix we have seen only the beginning of the compaction that must occur in

order to fit the chromosome into the cell nucleus. Unfortunately, the

higher-order structures of the compacted chromosome are still little

understood. The spools with their DNA somehow get packed into dense,

three-dimensional arrangements, and this entire arrangement coils further

upon itself beyond anyone's current ability to unravel the details. Such

difficulty, however, rarely hinders the adventurous from offering visual

models. So, for what it is worth, here is a conventional picture showing

several stages in the condensation of a chromosome (it is best viewed at

full screen width):

![[Images of (1) the double helix; (2) nucleosome; (3)

beads on a string; (4) 30 nanometer fiber; (5) active chromosome; and (6)

the chromosome during cell division.]](Images/chromosome1.jpg)

For credits and permissions, see

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4b/Chromatin_Structures.png.

During the cell's normal functioning the chromosome is not as fully

condensed as it is during cell division (the two images at far right).

Nor is it all in one state. Some parts of it — especially the parts

containing many active genes — are in something rather more like the

"beads-on-a-string" form, while other parts may be in the conformation of

the 30-nanometer fiber, and vast regions are in a much more wound-up form.

(Thirty nanometers is 30 billionths of a meter, or about 3 thousandths of

the diameter of a typical cell nucleus.) In general — but with

exceptions — the more compact the chromatin![]() , the less

available are the genes for transcription

, the less

available are the genes for transcription![]() .

.

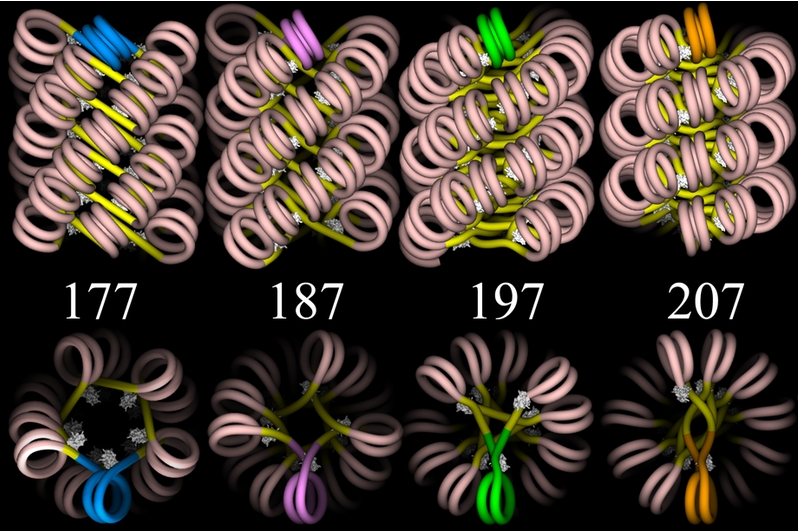

Another image follows below, this one showing four proposed models —

each viewed from two different angles — for the structure of

chromatin in the 30-nanometer fiber. The models do not show the actual

spools or other proteins, but only the DNA![]() . (The DNA is given as a simple "wire",

without any representation of the two helical strands.) However, you can

see how one spool could be positioned inside each double spiral of DNA.

Then, given the scale of the image, you would need to picture this

arrangement extending linearly for enormous distances, even if only a

small part of a chromosome were represented.

. (The DNA is given as a simple "wire",

without any representation of the two helical strands.) However, you can

see how one spool could be positioned inside each double spiral of DNA.

Then, given the scale of the image, you would need to picture this

arrangement extending linearly for enormous distances, even if only a

small part of a chromosome were represented.

Graphics by Julien Mozziconacci (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:ChromatinFibers.png) |

Linker DNA![]() — the

short, connecting lengths of DNA between spools — is shown in bright

yellow, and the wrapped DNA is flesh-colored. The different models are

based on different assumptions about the total number of base pairs

— the

short, connecting lengths of DNA between spools — is shown in bright

yellow, and the wrapped DNA is flesh-colored. The different models are

based on different assumptions about the total number of base pairs![]() from the

start of one spool to the start of the next one — that is, the

length of wrapped DNA plus linker DNA. These lengths are the numbers

shown in the figure. You can bring the upper and lower images into proper

relation if you imagine each of the upper images rotated ninety degrees

around a horizontal axis so as to bring the brightly colored (blue, pink,

green, or gold) double spiral of the upper image into the position shown

in the lower image. Finally, the white "lumps" in the figure represent

linker histones

from the

start of one spool to the start of the next one — that is, the

length of wrapped DNA plus linker DNA. These lengths are the numbers

shown in the figure. You can bring the upper and lower images into proper

relation if you imagine each of the upper images rotated ninety degrees

around a horizontal axis so as to bring the brightly colored (blue, pink,

green, or gold) double spiral of the upper image into the position shown

in the lower image. Finally, the white "lumps" in the figure represent

linker histones![]() , which hold

the DNA to the spool and help to stabilize the entire array.

, which hold

the DNA to the spool and help to stabilize the entire array.

Perhaps none of this helps us greatly to understand how the

extraordinarily long chromosome![]() ,

tremendously compacted to varying degrees along its length, can maintain

itself coherently within the functioning cell. But here's one relevant

consideration: there are enzymes called topoisomerases

,

tremendously compacted to varying degrees along its length, can maintain

itself coherently within the functioning cell. But here's one relevant

consideration: there are enzymes called topoisomerases![]() , whose task

is to help manage the forces and stresses within a chromosome.

Demonstrating a spatial insight and dexterity that might amaze those of us

who have struggled to sort out tangled masses of thread, these enzymes

manage to make just the right local cuts to the strands in order to

relieve strain, allow necessary movement of individual genes or regions of

the chromosome, and prevent a hopeless mass of knots.

, whose task

is to help manage the forces and stresses within a chromosome.

Demonstrating a spatial insight and dexterity that might amaze those of us

who have struggled to sort out tangled masses of thread, these enzymes

manage to make just the right local cuts to the strands in order to

relieve strain, allow necessary movement of individual genes or regions of

the chromosome, and prevent a hopeless mass of knots.

Some topoisomerases cut just one of the strands of the double helix![]() , allow it to

wind or unwind around the other strand, and then reconnect the severed

ends. Other topoisomerases cut both strands, pass a loop of the

chromosome through the gap thus created, and then seal the gap again.

(Imagine trying this with miles of string crammed into a tennis ball

— without tying the string into knots!) I don't think anyone would

claim to have the faintest idea how this is actually managed in a

meaningful, overall, contextual sense, but great and fruitful efforts are

being made to analyze isolated local forces and "mechanisms".

, allow it to

wind or unwind around the other strand, and then reconnect the severed

ends. Other topoisomerases cut both strands, pass a loop of the

chromosome through the gap thus created, and then seal the gap again.

(Imagine trying this with miles of string crammed into a tennis ball

— without tying the string into knots!) I don't think anyone would

claim to have the faintest idea how this is actually managed in a

meaningful, overall, contextual sense, but great and fruitful efforts are

being made to analyze isolated local forces and "mechanisms".

Before we try to bring the picture a little more alive, there's one small exercise that may help us. Many window shades have a looped cord for adjusting the light. If you slip your finger through the loop at the bottom and then twist it around in one direction many times, you will get our familiar double-stranded helix. Now, while keeping firm hold of the loop at the bottom, insert a pencil between the strands near the near the middle of the cord's length and then force the pencil downward. You will observe that the stands become progressively more tightly wound beneath your pencil, until it can move no more. At the same time the cord above the pencil becomes more loosely wound. Alternatively, you can let go the loop at the bottom, in which case the cord will spin around as the pencil descends.

This is relevant to the chromosome because when a gene is transcribed![]() , its two

double helical strands need to be separated, or "unzipped", as the

transcribing enzyme

, its two

double helical strands need to be separated, or "unzipped", as the

transcribing enzyme![]() moves along.

How, then, does the chromosome accommodate the twisting forces imposed by

this local "unzipping" of its two strands? You might expect the

chromosome to spin like the cord with a pencil moving down it. Certainly

there is some such movement. But if it were to proceed in an

unconstrained manner, as with the released window shade cord, the entire

chromosome ahead of the transcribing enzyme

moves along.

How, then, does the chromosome accommodate the twisting forces imposed by

this local "unzipping" of its two strands? You might expect the

chromosome to spin like the cord with a pencil moving down it. Certainly

there is some such movement. But if it were to proceed in an

unconstrained manner, as with the released window shade cord, the entire

chromosome ahead of the transcribing enzyme![]() would have

to make about 2850 complete turns during transcription of an average-sized

gene (Lavelle 2009), which means rotating at several turns per second.

Clearly, given the length, the mass, and the complex bending and looping

forms of the chromosome, and given the extremely thick "soup" of

macromolecules in the cell nucleus, such movement would be greatly

impeded.

would have

to make about 2850 complete turns during transcription of an average-sized

gene (Lavelle 2009), which means rotating at several turns per second.

Clearly, given the length, the mass, and the complex bending and looping

forms of the chromosome, and given the extremely thick "soup" of

macromolecules in the cell nucleus, such movement would be greatly

impeded.

Furthermore, the ends and many points within the chromosome are typically

"fastened down", as we will see later, so there isn't all that much

freedom of movement. Of course, when you move the pencil down between the

two strands of the window cord, you could allow the pencil itself to spin.

This would leave the helical structure of the cord mostly unchanged

outside the immediate vicinity of the pencil. However, in the cell our

"pencil" — the transcribing enzyme — is part of a very large

molecular complex. In addition, it is associated with a cumbersome set of

proteins for disassembling nucleosomes![]() ahead of its

transcribing activity, reassembling them behind, and performing various

other tasks. And it is attached to the ever-lengthening strand of RNA

ahead of its

transcribing activity, reassembling them behind, and performing various

other tasks. And it is attached to the ever-lengthening strand of RNA![]() that it is itself producing. So it

faces limits upon its mobility similar to those of the chromosome.

that it is itself producing. So it

faces limits upon its mobility similar to those of the chromosome.

The upshot of it all is that there are many complex movements, highly

constrained and absorbed in varying ways by the different resistant

elements of the complex structures involved. In general, positive

supercoiling![]() occurs ahead

of the transcribing enzyme's "unzipping" action and negative supercoiling

behind it. Topoisomerases play their role in managing both the stresses

and the overall conformation of the chromosome "tangle", as do many other

poorly characterized players in the sculptural drama of form and force

that is the chromosome.

occurs ahead

of the transcribing enzyme's "unzipping" action and negative supercoiling

behind it. Topoisomerases play their role in managing both the stresses

and the overall conformation of the chromosome "tangle", as do many other

poorly characterized players in the sculptural drama of form and force

that is the chromosome.

I have so far described the packaging of human DNA![]() as a mere technical challenge. That's a

big problem. The tensions and movements, the bending and unbending, the

coiling and uncoiling, are much more than the expression of mechanical

forces aimed at chromosome

as a mere technical challenge. That's a

big problem. The tensions and movements, the bending and unbending, the

coiling and uncoiling, are much more than the expression of mechanical

forces aimed at chromosome![]() condensation. It was quite wrong of me to begin by asking you to imagine

twisting a rope since, after all, there is no one — no specific

agent — in the cell nucleus performing this task. The chromosome is

not a passive, limp object moved only from outside. Interacting with its

surroundings, it is as much a living actor as any other part of its living

environment. Maybe instead of a rope, we should think of a snake,

coiling, curling, and sliding over a landscape that is itself in continual

movement.

condensation. It was quite wrong of me to begin by asking you to imagine

twisting a rope since, after all, there is no one — no specific

agent — in the cell nucleus performing this task. The chromosome is

not a passive, limp object moved only from outside. Interacting with its

surroundings, it is as much a living actor as any other part of its living

environment. Maybe instead of a rope, we should think of a snake,

coiling, curling, and sliding over a landscape that is itself in continual

movement.

The chromosome, in other words, is doing something. It is engaged in a highly effective spatial performance. It's movements are not simply the result of its being packaged and kept out of trouble, but rather are well-shaped responses to sensitively discerned needs. These movements bear decisive significance for the life of the cell and organism as a whole. Far better to picture the chromosome as both a sensing and muscular presence than as a rope.

To begin with, the mechanical stresses induced by transcription![]() are now

known to contribute broadly to gene regulation

are now

known to contribute broadly to gene regulation![]() . "The

organization of global transcription is tightly coupled to distribution of

supercoiling

. "The

organization of global transcription is tightly coupled to distribution of

supercoiling![]() sensitivity

in the genome"

sensitivity

in the genome"![]() (Blot 2006).

Increases in twist (positive supercoiling) are associated with chromatin

(Blot 2006).

Increases in twist (positive supercoiling) are associated with chromatin![]() folding and

gene silencing

folding and

gene silencing![]() in the

supercoiled region, whereas decreases of twist (negative supercoiling) are

associated with "acquisition of transcriptional competence" (Travers and

Muskhelishvili 2006). Moreover, "negative supercoils are dynamic. The

slithering and branching

in the

supercoiled region, whereas decreases of twist (negative supercoiling) are

associated with "acquisition of transcriptional competence" (Travers and

Muskhelishvili 2006). Moreover, "negative supercoils are dynamic. The

slithering and branching![]() of the

interwound strands allow DNA

of the

interwound strands allow DNA![]() to act like a chaperone

to act like a chaperone![]() , promoting

the long-range assembly and disassembly of protein-DNA complexes" (Deng et

al. 2005) — complexes that play a vital role in gene regulation.

Each type of cell has its own characteristic patterns of supercoiling,

which is doubtless related to the fact that it also has its own

distinctive patterns of gene expression

, promoting

the long-range assembly and disassembly of protein-DNA complexes" (Deng et

al. 2005) — complexes that play a vital role in gene regulation.

Each type of cell has its own characteristic patterns of supercoiling,

which is doubtless related to the fact that it also has its own

distinctive patterns of gene expression![]() . Christophe

Lavelle of the Curie Institute in France summarizes the recent research

findings this way:

. Christophe

Lavelle of the Curie Institute in France summarizes the recent research

findings this way:

As DNA is rotating inside the polymerase[transcribing enzyme], positive and negative supercoiling is induced downstream and upstream

, respectively. Transcriptionally generated torsion, rather than a mere waste product to be disposed of by topoisomerases, has instead recently been shown to propagate through the chromatin fiber and trigger local DNA alterations, detected as a regulatory signal by molecular partners. (Lavelle 2009)

To illustrate the regulatory possibilities: researchers at the National

Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, found that negative supercoiling![]() upstream

(behind) a transcribing enzyme was sufficient to cause a local,

nonstandard conformation of the double helix

upstream

(behind) a transcribing enzyme was sufficient to cause a local,

nonstandard conformation of the double helix![]() , which in

turn enabled recruitment of regulatory proteins sensitive to such changes

in structure (Kouzine et al. 2008).

, which in

turn enabled recruitment of regulatory proteins sensitive to such changes

in structure (Kouzine et al. 2008).

So the chromosome's twisting and writhing is not merely arbitrary; it is sculpturally significant movement, carrying meaning for the chromosomal stretches along which it is communicated.

But there are many other dimensions of the chromosome's![]() spatial

performance. Each chromosome has its own preferred territory within the

nucleus and its preferred neighbors, which also differ from one cell type

to another. These territories "are dynamic and plastic structures" that

"can be dynamically repositioned" (Schneider and Grosschedl 2007). Since

living conditions are close, the neighbors matter. A chromosome's

territory appears to be shaped rather like an irregular potato or a

sponge. There is at least some socializing between adjacent chromosomes,

with protrusions of one territory penetrating into the hollowed-out

portions of the next territory and even of more remote territories (Ling

et al. 2007). So not only are distantly separated portions of the same

chromosome brought into intimate contact by the geometry of the sponges,

but loci on separate chromosomes can also be brought into contact.

spatial

performance. Each chromosome has its own preferred territory within the

nucleus and its preferred neighbors, which also differ from one cell type

to another. These territories "are dynamic and plastic structures" that

"can be dynamically repositioned" (Schneider and Grosschedl 2007). Since

living conditions are close, the neighbors matter. A chromosome's

territory appears to be shaped rather like an irregular potato or a

sponge. There is at least some socializing between adjacent chromosomes,

with protrusions of one territory penetrating into the hollowed-out

portions of the next territory and even of more remote territories (Ling

et al. 2007). So not only are distantly separated portions of the same

chromosome brought into intimate contact by the geometry of the sponges,

but loci on separate chromosomes can also be brought into contact.

It happens that both sorts of contact have a great deal to do with gene

expression![]() . On an

earlier view, the DNA sequences

. On an

earlier view, the DNA sequences![]() regulating a

protein-coding gene were always close to the gene or at least not very far

removed. But in more recent years it's been recognized that some

regulatory sites — "enhancers"

regulating a

protein-coding gene were always close to the gene or at least not very far

removed. But in more recent years it's been recognized that some

regulatory sites — "enhancers"![]() and

"silencers"

and

"silencers"![]() and "locus

control regions"

and "locus

control regions"![]() — may

be located on distant parts of the chromosome, thousands or hundreds of

thousands or even millions of base pairs

— may

be located on distant parts of the chromosome, thousands or hundreds of

thousands or even millions of base pairs![]() away from

the gene being regulated

away from

the gene being regulated![]() . Expression

is enabled, for example, when the distant enhancer is brought into

physical proximity with the gene or genes it regulates. (Another

remarkable feat of contextually apt physical coordination!) In connection

with this, an activator

. Expression

is enabled, for example, when the distant enhancer is brought into

physical proximity with the gene or genes it regulates. (Another

remarkable feat of contextually apt physical coordination!) In connection

with this, an activator![]() protein is

bound to the enhancer and then, perhaps in concert with one or more

co-activators

protein is

bound to the enhancer and then, perhaps in concert with one or more

co-activators![]() , may assist

in constellating the massive transcription complex

, may assist

in constellating the massive transcription complex![]() on the

gene's promoter

on the

gene's promoter![]() sequence

sequence![]() .

.

A locus control region![]() (LCR) is a

DNA

(LCR) is a

DNA![]() sequence

that helps to regulate a cluster of related genes. One research team in

the Netherlands, working with mice, examined an LCR for a set of genes

relating to the production of beta-globin (a constituent of hemoglobin).

In fetal liver tissue, where these genes are highly active, the LCR was

found to associate with dozens of genes, including many involved in

beta-globin production. Some of these genes were tens of millions of base

pairs

sequence

that helps to regulate a cluster of related genes. One research team in

the Netherlands, working with mice, examined an LCR for a set of genes

relating to the production of beta-globin (a constituent of hemoglobin).

In fetal liver tissue, where these genes are highly active, the LCR was

found to associate with dozens of genes, including many involved in

beta-globin production. Some of these genes were tens of millions of base

pairs![]() distant on

the chromosome. Further, in fetal brain tissue, where the beta-globin

genes are inactive, the LCR again associated with many other sites —

but now a completely different set. The researchers concluded:

distant on

the chromosome. Further, in fetal brain tissue, where the beta-globin

genes are inactive, the LCR again associated with many other sites —

but now a completely different set. The researchers concluded:

Our observations demonstrate that not only active, but also inactive, genomic regions can transiently interact over large distances with many loci in the nuclear space. The data strongly suggest that each DNA segment has its own preferred set of interactions. This implies that it is impossible to predict the long-range interaction partners of a given DNA locus without knowing the characteristics of its neighboring segments and, by extrapolation, the whole chromosome. (Simonis et al. 2006)

It's not only where loci on a single chromosome![]() are brought

into contact with each other that they can interact, however. Increasing

numbers of cases are being reported where contact between sites on

different chromosomes plays a crucial role in gene regulation

are brought

into contact with each other that they can interact, however. Increasing

numbers of cases are being reported where contact between sites on

different chromosomes plays a crucial role in gene regulation![]() . In fact,

the mouse study just cited demonstrated a number of such contacts. (A few

researchers began to speak of "kissing chromosomes" — a not very

helpful phrase that seems now to have been dropped from the literature.)

Here's a schematic representation of one case of interchromosomal

interaction. (Skip the next three paragraphs if you don't want to bother

with the technical details.)

. In fact,

the mouse study just cited demonstrated a number of such contacts. (A few

researchers began to speak of "kissing chromosomes" — a not very

helpful phrase that seems now to have been dropped from the literature.)

Here's a schematic representation of one case of interchromosomal

interaction. (Skip the next three paragraphs if you don't want to bother

with the technical details.)

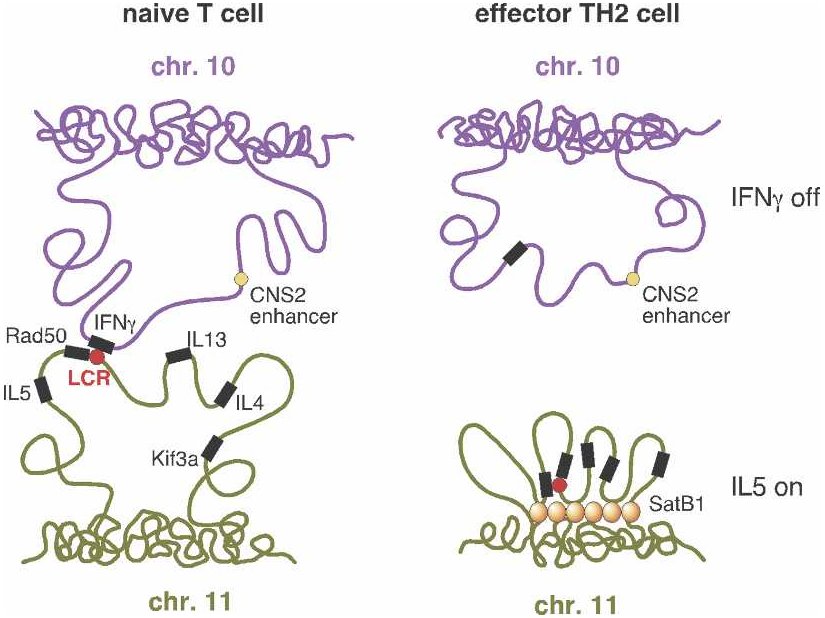

From Schneider and Grosschedl 2007. |

"T helper" or TH cells are human immune system cells. One type of TH cell (TH1) produces, among other things, interferon (IFN-gamma), while a second type (TH2) produces various interleukins such as IL-4 and IL-5. But before a cell becomes either a TH1 or TH2, it resides in a less differentiated state as a "naive" TH cell (referred to as a "T cell" in the figure). Only after stimulation by an antigen (a substance that provokes formation of antibodies), does the TH cell become either a TH1 or TH2 cell.

If you look at the genes responsible for producing interferon in TH1 and

interleukins in TH2 cells, you find the usual suspects: the interferon

gene on chromosome 10 seems to be regulated by nearby genomic elements,

while the interleukin genes on chromosome 11 are also regulated by local

sites — in particular, by an LCR![]() . But a research team at the Yale

University School of Medicine decided to investigate the larger spatial

picture. They discovered that regulatory regions

. But a research team at the Yale

University School of Medicine decided to investigate the larger spatial

picture. They discovered that regulatory regions![]() associated

with the interferon and interleukin genes, despite being on separate

chromosomes, were physically close together in naive cells. Upon

stimulation of naive cells by an antigen, the "negotiations" between these

regulatory regions somehow determined which of the genes would be active

and which would be repressed — and therefore whether the cell would

become a TH1 or TH2 cell. Following this determination, the two

chromosome regions moved apart.

associated

with the interferon and interleukin genes, despite being on separate

chromosomes, were physically close together in naive cells. Upon

stimulation of naive cells by an antigen, the "negotiations" between these

regulatory regions somehow determined which of the genes would be active

and which would be repressed — and therefore whether the cell would

become a TH1 or TH2 cell. Following this determination, the two

chromosome regions moved apart.

The illustration (right side) shows the case where a TH2 cell has

resulted. Interferon (IFN-gamma) is not expressed![]() (upper

right) because the looping pattern separates the requisite gene from its

enhancer

(upper

right) because the looping pattern separates the requisite gene from its

enhancer![]() . On the

other hand, IL-5 is expressed (lower right), because the protein

SATB1, which plays a large role in chromatin

. On the

other hand, IL-5 is expressed (lower right), because the protein

SATB1, which plays a large role in chromatin![]() organization

and transcription

organization

and transcription![]() regulation,

has anchored a series of chromosome loops in just such a way as to bring

the IL-5 gene and Rad50 promoter

regulation,

has anchored a series of chromosome loops in just such a way as to bring

the IL-5 gene and Rad50 promoter![]() into

proximity with the locus control region. (Spilianakis et al. 2005; see

also commentary in Kioussis 2005.)

into

proximity with the locus control region. (Spilianakis et al. 2005; see

also commentary in Kioussis 2005.)

Of course, as researchers dealing with this sort of thing readily acknowledge, questions abound. What guides particular sites on two different chromosomes to their rendezvous, and what sees to their subsequent separation? One could imagine, in the case of distantly separated sites on the same chromosome, that a regulatory protein binds to the one locus and then "tracks" along the chromosome until it finds the second locus (which it must have some way to recognize as significantly related to the first). But it's not at all easy to picture what it is that selects and brings together many loci on different chromosomes.

As is evident from the case of TH cells, chromosome looping can keep sites

apart as well as bring them together. It not only serves the purpose of

expression![]() , but also of

repression

, but also of

repression![]() . In a study

of red blood cells, a group of scientists from Children's Hospital in

Philadelphia showed that successive stages of cell maturation were marked

by different proteins playing a direct role in reconfiguring chromosome

loops — first for expression of a particular gene, and later for

repression (Jing et al. 2008). In general, chromosome loops help to make

possible the more or less independent regulation of different gene regions

— an important role in an environment thick with diverse regulatory

factors and processes.

. In a study

of red blood cells, a group of scientists from Children's Hospital in

Philadelphia showed that successive stages of cell maturation were marked

by different proteins playing a direct role in reconfiguring chromosome

loops — first for expression of a particular gene, and later for

repression (Jing et al. 2008). In general, chromosome loops help to make

possible the more or less independent regulation of different gene regions

— an important role in an environment thick with diverse regulatory

factors and processes.

But how does a locus on a chromosome![]() "take off"

through the three-dimensional space of the nucleus, uncoiling from a more

condensed state into a thin thread and looping outward from its territory

for considerable distances, as if drawn by an invisible hand toward a

rendezvous with a distant location? One group of researchers positioned a

transcriptional activator

"take off"

through the three-dimensional space of the nucleus, uncoiling from a more

condensed state into a thin thread and looping outward from its territory

for considerable distances, as if drawn by an invisible hand toward a

rendezvous with a distant location? One group of researchers positioned a

transcriptional activator![]() on a

particular chromosomal site located close to the periphery of the cell

nucleus. Within 1 - 2 hours, the site migrated to the interior of the

nucleus, following a curvilinear path roughly perpendicular to the nuclear

envelope

on a

particular chromosomal site located close to the periphery of the cell

nucleus. Within 1 - 2 hours, the site migrated to the interior of the

nucleus, following a curvilinear path roughly perpendicular to the nuclear

envelope![]() . The

movement, which was interspersed with several-minute periods of

quiescence, reached a maximum velocity of about 1/10 the nuclear diameter

per minute. These results led the researchers to speak of "fast and

directed long-range chromosome movements" (Chuang et al. 2006).

. The

movement, which was interspersed with several-minute periods of

quiescence, reached a maximum velocity of about 1/10 the nuclear diameter

per minute. These results led the researchers to speak of "fast and

directed long-range chromosome movements" (Chuang et al. 2006).

A fairly recent surprise has been the discovery of actin and myosin in connection with some chromosome movements. These two substances, which play a major role in the contraction of muscles, seem also to provide a kind of "musculature" within the nucleus. Get rid of them, and certain observed movements stop. But little is yet known about how the movement is actually achieved, and even less about how it is directed.

What is now known, however, is that the nucleus is much more than a

linear assembly line for the construction of proteins based on genetic

sequences![]() . It

participates in an elaborately organized, three-dimensional space, and the

positioning and movement of both chromosomes and the regulatory elements

within the nucleus have everything to do with the functioning of the

genome

. It

participates in an elaborately organized, three-dimensional space, and the

positioning and movement of both chromosomes and the regulatory elements

within the nucleus have everything to do with the functioning of the

genome![]() .

.

But while extraordinary research energies are now directed toward

articulating the undeniable structural organization of the cell nucleus in

its relation to gene regulation![]() , an overall,

coherent picture of the organization remains elusive. The titles of

several articles currently lying on my desk point to the challenge

investigators face:

, an overall,

coherent picture of the organization remains elusive. The titles of

several articles currently lying on my desk point to the challenge

investigators face:

"Dynamics and Interplay of Nuclear Architecture, Genome Organization, and Gene Expression" (Schneider and Grosschedl 2007)."Dynamic Genome Architecture in the Nuclear Space: Regulation of Gene Expression in Three Dimensions" (Lanctôt et al. 2007).

"The Third Dimension of Gene Regulation: Organization of Dynamic Chromatin Loopscape by SATB1" (Galande et al. 2007).

"Dynamic Regulation of Nucleosome Positioning in the Human Genome" (Schones et al. 2008).

"Dynamic Organization of Gene Loci and Transcription Compartments in the Cell Nucleus" (Spudich 2008).

"Nuclear Functions in Space and Time: Gene Expression in a Dynamic, Constrained Environment" (Trinkle-Mulcahy and Lamond 2008).

You will have noted the repeated juxtaposition — spatial

organization on the one hand, dynamism on the other. How does one capture

organization that is dynamic and ever-shifting? The question only becomes

more acute when we look at a few additional aspects of nuclear

organization, as currently described in the literature:

Chromosome Domains. Chromosomes![]() , as we have

seen, participate in the highly structured space of the nucleus. But that

is not all. They themselves are structured along their length, being

subdivided by various means and in ever-changing ways into chromosome

domains. We've already seen the organization of the chromosome into

densely compacted regions (known as heterochromatin

, as we have

seen, participate in the highly structured space of the nucleus. But that

is not all. They themselves are structured along their length, being

subdivided by various means and in ever-changing ways into chromosome

domains. We've already seen the organization of the chromosome into

densely compacted regions (known as heterochromatin![]() ) and less

condensed, more active regions (euchromatin

) and less

condensed, more active regions (euchromatin![]() ). The

boundaries between such regions are not always well-defined. Simply by

residing close to a region of heterochromatin, a gene that otherwise would

be very actively transcribed

). The

boundaries between such regions are not always well-defined. Simply by

residing close to a region of heterochromatin, a gene that otherwise would

be very actively transcribed![]() might be

only intermittently expressed

might be

only intermittently expressed![]() , or even

silenced

, or even

silenced![]() altogether.

Where somewhat more cleanly separate regulation of neighboring loci is

important, special DNA sequences

altogether.

Where somewhat more cleanly separate regulation of neighboring loci is

important, special DNA sequences![]() called

insulators

called

insulators![]() can help

prevent the "leaking" of influence from one region of the chromosome to

the next.

can help

prevent the "leaking" of influence from one region of the chromosome to

the next.

Chromosome domains are also established by the twisting forces (torsion)

communicated more or less freely along bounded segments of the chromosome.

(The boundaries might be defined, for example, by the tethering points of

chromosome loops.) The loci within such a region share a common torsion,

and this can attract a common set of regulatory proteins. The torsion

also tends to correlate with the level of compaction of the chromatin

fiber, which in turn correlates with many other aspects of gene

regulation![]() . And even

on an extremely small scale, the twisting (by linker histones

. And even

on an extremely small scale, the twisting (by linker histones![]() ) of the

short stretches of DNA between nucleosomes

) of the

short stretches of DNA between nucleosomes![]() — or

the untwisting brought about by the release of the histones — is

presumed to drive the folding or unfolding of the local chromatin

— or

the untwisting brought about by the release of the histones — is

presumed to drive the folding or unfolding of the local chromatin![]() (Travers and

Muskhelishvili 2006). All this reminds us that gene regulation is defined

less by static entities than by the quality and force of various

movements.

(Travers and

Muskhelishvili 2006). All this reminds us that gene regulation is defined

less by static entities than by the quality and force of various

movements.

There are still other ways that the chromosome reveals itself as a dynamic, complexly structured context. Genes expressed in the same cell type or at the same time, genes sharing common regulatory factors, and genes actively expressed (or mostly inactive) tend to be grouped together. One way such domains could be established is through the binding of the same protein complexes along a region of the chromosome, thereby establishing a common molecular and regulatory environment for the encompassed genes. But it's important to realize that such regions are more a matter of tendency than of absolute rule. A few examples from a summary by Elzo de Wit and Bas van Steensel at the Netherlands Cancer Institute illustrate the situation:

These rough tendencies do not enable precise predictions, but yet the

tendencies are really there; they point toward meaningful organization,

even though the observed "rules" are less the determiners of that

organization than they are the continually modified products of it. This

is exactly what you would expect in any living context, where a larger

unity — the unity that leads us to refer quite naturally to a

living being — shapes the activity of local parts and

processes to its own intention.

The "Pull" of the Nuclear

Periphery. There is a fibrous network — the "nuclear lamina"

— located primarily at the inside face of the nuclear envelope.

In vitro studies (what used to be referred to as "test-tube

studies") have shown that several proteins of this network can interact

with chromatin![]() . And now,

as the Dutch biologists summarize, it has been found that there are more

than 1300 lamina-associated chromosome domains (LADs) in the human

genome

. And now,

as the Dutch biologists summarize, it has been found that there are more

than 1300 lamina-associated chromosome domains (LADs) in the human

genome![]() that do

indeed preferentially locate themselves at the nuclear periphery. De Wit

and van Steensel (2009) mention studies showing that the artificial

anchoring of a chromosome

that do

indeed preferentially locate themselves at the nuclear periphery. De Wit

and van Steensel (2009) mention studies showing that the artificial

anchoring of a chromosome![]() locus to the

nuclear lamina "can cause partial downregulation of some (but not all)

genes surrounding the anchoring sequence

locus to the

nuclear lamina "can cause partial downregulation of some (but not all)

genes surrounding the anchoring sequence![]() ".

".

There seems to be a general rule that the chromosomes and chromosome

territories located toward the periphery of the nucleus are less

transcriptionally![]() active and

also less gene-dense. Conversely, the nuclear interior shows higher rates

of activity and greater gene density. Researchers can activate

active and

also less gene-dense. Conversely, the nuclear interior shows higher rates

of activity and greater gene density. Researchers can activate![]() genes near

the nuclear envelope and then watch them as they move toward the interior.

Likewise, they can silence

genes near

the nuclear envelope and then watch them as they move toward the interior.

Likewise, they can silence![]() genes in the

interior and watch them relocating to the periphery. Nevertheless,

transcription does occur in the outlying regions, and silent regions of

chromosomes reside in the interior. And, as always, multiple dimensions

of regulation work together. For example, the radial positioning of genes

seems to be connected to specific histone modifications

genes in the

interior and watch them relocating to the periphery. Nevertheless,

transcription does occur in the outlying regions, and silent regions of

chromosomes reside in the interior. And, as always, multiple dimensions

of regulation work together. For example, the radial positioning of genes

seems to be connected to specific histone modifications![]() of the sort

we looked at in Part 1 — although it's a matter of rough rather than

absolutely consistent correlation (Strašák et al. 2009).

of the sort

we looked at in Part 1 — although it's a matter of rough rather than

absolutely consistent correlation (Strašák et al. 2009).

Nuclear Matrix. It is not only the peripheral nuclear lamina that

provides a kind of skeletal structure for organizing the nucleus. There

is, throughout the nuclear space, a still poorly characterized and elusive

"nuclear matrix" — so elusive that its fundamental nature is still

debated. The nuclear lamina![]() can be

considered part of it, and there are many other substances that seem to

play a role, including the SATB1 protein we encountered in connection with

looping chromosomes, a topoisomerase

can be

considered part of it, and there are many other substances that seem to

play a role, including the SATB1 protein we encountered in connection with

looping chromosomes, a topoisomerase![]() , actin

, actin![]() , and even

the DNA transcribing

, and even

the DNA transcribing![]() and

replication

and

replication![]() enzymes.

Many of the proteins that associate with chromatin

enzymes.

Many of the proteins that associate with chromatin![]() , affecting

its form and compaction, are considered to be components of the nuclear

matrix. In other words, the nuclear matrix is not simply a passive

structure that objects can attach to. It consists of active agents

— and, in our current context, that means agents of gene

regulation

, affecting

its form and compaction, are considered to be components of the nuclear

matrix. In other words, the nuclear matrix is not simply a passive

structure that objects can attach to. It consists of active agents

— and, in our current context, that means agents of gene

regulation![]() .

.

The human genome![]() contains an

estimated 30,000-80,000 "matrix attachment regions" (MARs) —

relatively short DNA sequences susceptible of being anchored to the

nuclear matrix (Ottaviani et al. 2008). These anchoring points can

contribute to the formation of the loops we've been talking about. Some

MARs are more or less permanently attached to the matrix and may be

associated with higher-order chromatin

contains an

estimated 30,000-80,000 "matrix attachment regions" (MARs) —

relatively short DNA sequences susceptible of being anchored to the

nuclear matrix (Ottaviani et al. 2008). These anchoring points can

contribute to the formation of the loops we've been talking about. Some

MARs are more or less permanently attached to the matrix and may be

associated with higher-order chromatin![]() compaction

and the repression

compaction

and the repression![]() of genes not

required in a particular cell type. Others only transiently attach to the

matrix and are thought to play a major role in the management of gene

expression

of genes not

required in a particular cell type. Others only transiently attach to the

matrix and are thought to play a major role in the management of gene

expression![]() . The

configuration of attachments at any given moment shapes the overall

chromosome architecture, and the consequent looping patterns effectively

insulate some regions from regulatory factors while exposing others. In

sum:

. The

configuration of attachments at any given moment shapes the overall

chromosome architecture, and the consequent looping patterns effectively

insulate some regions from regulatory factors while exposing others. In

sum:

Our understanding of how the genome functions in the context of the nucleus has been propelled by indisputable evidence that distinct genomic sites bind to regulatory proteins at the nuclear matrix. The emerging picture is that these genomic anchors regulate transcriptionand replication

by dynamically organizing chromatin in three-dimensional space. (Ottaviani et al. 2008)

By this time I'm sure you recognize the need to ask (upon hearing that

genomic anchors "regulate transcription"): What is it that regulates the

anchors? How do they know when and where and for how long to participate

in their anchoring task? The point, which is one of our enduring themes

in these articles, is that there is no single, controlling level of gene

regulation, subordinating the rest of the organism to itself. Noting that

"the existence of regulatory cross-talk between spatially interacting loci

opens up a new dimension in the study of gene regulation", Christian

Lanctôt et al. (2007) go on to remark that "not only does [this

cross-talk] constitute an additional level of complexity in the search for

regulatory elements in the genome![]() , it also

implies that chromatin

, it also

implies that chromatin![]() mobility

itself, and therefore the ensuing long-range gene-gene interactions, might

be a target of regulation".

mobility

itself, and therefore the ensuing long-range gene-gene interactions, might

be a target of regulation".

How could it be otherwise within a harmoniously functioning organism? I

suspect it's quite safe to say that every aspect of the cell is in one way

or another a target of regulation, and at the same time takes on some of

the role of regulator. Or better (since that last statement reduces the

word "regulation" to something close to nonsense): every part participates

in the whole organism and is informed by the whole. Of course, in the

current state of biology this remark, too, will strike many as nonsense.

One could reply by asking whether it's any more nonsensical than

all the usual talk of "regulation", but a more positive approach would be

to take up the question of holism, as we will do later in this series.

Nuclear Compartments and Organelles. Loops are created

when separate points on a chromosome![]() are brought

together and at least temporarily bound at the same location.

Multiple-loop structures result when a number of different loci fraternize

in this way. This raises the question: in what sense are the regions

where these gatherings occur "real places"? That is, what structural

identity do they possess beyond the fact that they happen to be sites

where active chromosomal loci have gathered?

are brought

together and at least temporarily bound at the same location.

Multiple-loop structures result when a number of different loci fraternize

in this way. This raises the question: in what sense are the regions

where these gatherings occur "real places"? That is, what structural

identity do they possess beyond the fact that they happen to be sites

where active chromosomal loci have gathered?

In one sense, the answer is easy. In order for genes to be active, there

must be transcribing enzymes![]() and many

other factors related to transcription

and many

other factors related to transcription![]() . So it

stands to reason that these centers of activity are distinctively

constituted. High-resolution surveys of the cell nucleus do in fact show

many such places, which have come to be called transcription "factories"

(a rather prejudicial term). Estimates for their number range from 500 to

10,000 (Trinkle-Mulcahy 2008), and it has been conjectured that, on

average, some eight transcribing enzymes are present in each center of

activity.

. So it

stands to reason that these centers of activity are distinctively

constituted. High-resolution surveys of the cell nucleus do in fact show

many such places, which have come to be called transcription "factories"

(a rather prejudicial term). Estimates for their number range from 500 to

10,000 (Trinkle-Mulcahy 2008), and it has been conjectured that, on

average, some eight transcribing enzymes are present in each center of

activity.

One group of researchers, describing how distantly separated genes in red

blood cells "colocalize to the same transcription factory at high

frequencies", go on to summarize the situation: "active genes are

dynamically organized into shared nuclear subcompartments and movement

into or out of these factories results in activation or abatement of

transcription. Thus, rather than recruiting and assembling transcription

complexes, active genes migrate to preassembled transcription sites"

(Osborne et al. 2004). The implication, noted by the authors, is that

"mechanisms regulating recruitment of genes into factories would be

expected to have a fundamental role in gene expression![]() ".

".

The transcribing enzymes![]() in (or,

rather, at the outer surface of) the active transcription centers,

according to the emerging view, do not themselves move along the genes;

they "reel in" the genes they are transcribing. In this way they act as

critical structural elements for maintaining the loops, which come and go

as the various enzymes and regulatory factors bind and release them

(Carter et al. 2008).

in (or,

rather, at the outer surface of) the active transcription centers,

according to the emerging view, do not themselves move along the genes;

they "reel in" the genes they are transcribing. In this way they act as

critical structural elements for maintaining the loops, which come and go

as the various enzymes and regulatory factors bind and release them

(Carter et al. 2008).

But, still, uncertainty remains about how much "there" is really there in

the transcription centers. To what degree do enduring structures exist

apart from the organized "structure" of the ongoing processes of

transcription? There is presumably something there, but it's

proven subtle and difficult to pin down. The matrix attachment regions![]() of chromosomes, which presumably play a

role in bringing genes to transcriptional centers, are being identified,

but it remains to find anything in the way of a very fixed and definite

structure for them to attach to. The "structure", such as it is, seems to

be as much process as product.

of chromosomes, which presumably play a

role in bringing genes to transcriptional centers, are being identified,

but it remains to find anything in the way of a very fixed and definite

structure for them to attach to. The "structure", such as it is, seems to

be as much process as product.

There are yet other nuclear compartments relating to gene expression, but we will not pursue them here.

The intricately formed activity of the nucleus varies from one cell type

to another and from one stage of an organism's development to another. It

both shapes and mirrors the distinctive character of the individual cell.

But this character is not some abstract essence detached from whatever

else is going on in the organism at a particular moment. We can only

assume that, whether the cat we are looking at is stalking or eating or

sleeping or raising its fur in a confrontation with an enemy, the

expressive differences we can recognize in these activities would be

matched by expressive differences at every level of the cat's life,

including the level of gene transcription![]() and nuclear

organization — if only we were capable of reading the cell with the

same qualitative attention we devote to the outward behavior of the cat.

If the cat is raising its fur, then the skin, muscle, and other cells must

in some sense be "raising their fur" as well.

and nuclear

organization — if only we were capable of reading the cell with the

same qualitative attention we devote to the outward behavior of the cat.

If the cat is raising its fur, then the skin, muscle, and other cells must

in some sense be "raising their fur" as well.

In other words, the chromosome![]() movements

we've looked at are always part of the larger activity of the organism.

It's not just that a locus of the chromosome moves from point A to point B

in order to connect with a group of other loci; this process in

turn takes place in order to achieve equally significant

performances at higher levels of observation, whether it's a matter of the

cell's response to a nearby lesion or to starvation or to the organism's

emotional state. The activities in the cell nucleus are part of an

overall organic picture, and the scientist will do well to remember

occasionally how remote is the detailed knowledge of the sort I've

outlined above from any coherent and contextual understanding of what's

going on.

movements

we've looked at are always part of the larger activity of the organism.

It's not just that a locus of the chromosome moves from point A to point B

in order to connect with a group of other loci; this process in

turn takes place in order to achieve equally significant

performances at higher levels of observation, whether it's a matter of the

cell's response to a nearby lesion or to starvation or to the organism's

emotional state. The activities in the cell nucleus are part of an

overall organic picture, and the scientist will do well to remember

occasionally how remote is the detailed knowledge of the sort I've

outlined above from any coherent and contextual understanding of what's

going on.

This is presumably why biologists Amy Hark and Steven Triezenberg (2001), speaking of the variety of protein complexes affecting chromatin structure and gene expression, point to "a web of functional interactions that might be viewed as either elegantly integrated or hopelessly tangled". Hopelessly tangled, that is, if we do no more than lose ourselves in tracking isolated "causal factors" and "effects"; elegantly integrated if we can somehow rise to a more pictorial and qualitative grasp of what clearly is in fact a unified whole.

Perhaps we have the most incentive to seek such a wider understanding when we confront disease. There is no doubt, for example, that the phenomena investigated by the epigeneticist bear heavily on cancer, even if there is little effort as yet to read the cell as an expressive whole. Certainly research into particular "mechanisms" is proceeding at full tilt. Referring to how the microenvironments of the nucleus bring together the various gene-regulatory signals in all their necessary combinations, one team of researchers reviews the implications for cancer diagnosis and treatment:

Solid tumours, leukaemias, and lymphomas show striking alterations in nuclear morphology as well as in the architectural organization of genes, transcriptsThe researchers add that the effects of therapeutic treatment hang in the balance of these complex interactions, since even a patient's sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy depends on the "composition, assembly and architectural organization of regulatory machinery within the cancer cell nucleus". The hope, finally, is that the "functional relationship between nuclear organization and gene expression, and regulatory

complexes within the nucleus. . . . These cancer-related changes disrupt several levels of nuclear organization that include linear gene sequences, chromatin

organization and subnuclear [compartments]. . . . Modifications in chromatin remodelling complexes

, the persistent association of regulatory proteins with gene loci, and DNA methylation

epigenetically modulate genome

accessibility to regulatory factors for the physiological control of cell fate.... (Zaidi et al. 2007).

That hope may sooner or later be fulfilled. But the scale of the challenge looks hard to underestimate!

In any case, the fluid spatial organization of the nucleus and the

movement of chromosomes![]() within it

clearly play a vital role in bringing about the right "marriages" between

participants in the intricate playing out of genomic expression —

and also in avoiding the wrong marriages. The evidence suggests,

according to UK geneticists Peter Fraser and Wendy Bickmore, that "the

dynamic spatial organization of the nucleus both reflects and shapes

genome

within it

clearly play a vital role in bringing about the right "marriages" between

participants in the intricate playing out of genomic expression —

and also in avoiding the wrong marriages. The evidence suggests,

according to UK geneticists Peter Fraser and Wendy Bickmore, that "the

dynamic spatial organization of the nucleus both reflects and shapes

genome![]() function. . . . We now have a picture of a genome that

is 'structured', not in a rigid three-dimensional network, but in a

dynamic organization [that] clearly changes during normal development

function. . . . We now have a picture of a genome that

is 'structured', not in a rigid three-dimensional network, but in a

dynamic organization [that] clearly changes during normal development![]() and

differentiation"

and

differentiation"![]() (Fraser and

Bickmore 2007).

(Fraser and

Bickmore 2007).

We began by asking ourselves how the cell condenses two meters of DNA![]() into a nucleus ten millionths of a meter

in diameter. The question is justified, but we can see by now that it's

hardly a mere matter of avoiding a snarled state so that an autonomous

logic of transcription

into a nucleus ten millionths of a meter

in diameter. The question is justified, but we can see by now that it's

hardly a mere matter of avoiding a snarled state so that an autonomous

logic of transcription![]() can proceed

along its fated way. The adroit dynamics and deft sculpturing of

chromosomes and an entire galaxy of proteins are as much the "whole point

of the show" as any fixed code. The logic of transcription itself is, at

least in part, a disciplined art of movement. The next time you find

yourself picturing heredity as the transmission of fixed, determinative

elements from parent to offspring, you might pause to ask yourself how

such statically imagined elements could determine the art of movement that

also comes to expression in successive generations.

can proceed

along its fated way. The adroit dynamics and deft sculpturing of

chromosomes and an entire galaxy of proteins are as much the "whole point

of the show" as any fixed code. The logic of transcription itself is, at

least in part, a disciplined art of movement. The next time you find

yourself picturing heredity as the transmission of fixed, determinative

elements from parent to offspring, you might pause to ask yourself how

such statically imagined elements could determine the art of movement that

also comes to expression in successive generations.

There is, after all, as much cause and effect, as much determination of

outcomes, as much logic and reason, in the compaction and twisting,

the movement and re-shaping, as there is in any other aspect of the cell

nucleus, even if the dynamism is fluid and irreducible to digital terms.

The chromosome performs an unceasing dance and — crucially —

the ever-shifting pattern of the dance lends its form and organization