NETFUTURE

Technology and Human Responsibility

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Issue #164 July 5, 2005

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

A Publication of The Nature Institute

Editor: Stephen L. Talbott (stevet@netfuture.org)

On the Web: http://netfuture.org

You may redistribute this newsletter for noncommercial purposes.

Can we take responsibility for technology, or must we sleepwalk

in submission to its inevitabilities? NetFuture is a voice for

responsibility. It depends on the generosity of those who support

its goals. To make a contribution, click here.

CONTENTS

---------

Editor's Note

Can We Learn to Think Like a Plant? (Stephen L. Talbott)

Toward a New, Qualitative Science (Part 2)

DEPARTMENTS

About this newsletter

==========================================================================

EDITOR'S NOTE

Issue #13 of The Nature Institute's hardcopy publication, In Context,

is now available. Its feature articles, posted online, include "From

Two Cultures to One: On the Relation Between Science and Art", which

I co-wrote with Vladislav Rozentuller. This essay relates closely to

the pieces I have been presenting in NetFuture on qualitative science,

and tries to show how human experience provides a language of revelation

for the physical world. The latest In Context also contains an

assessment by neurologist Siegward Elsas of the relation between brain

activity and thinking. You will find both articles at

http://natureinstitute.org/pub/ic/ic13.

One other thing. Some of you may be interested in The Nature Institute's

one-week intensive summer course, "Reading the Gestures of Life", July 10

- 16. This is an introduction to the methods of Goethean, or qualitative,

science, led by my biologist-colleague, Craig Holdrege. For details, go

to http://natureinstitute.org/ni/educ/summer. If you want to participate,

we'll need to hear from you by Friday.

SLT

Goto table of contents

==========================================================================

CAN WE LEARN TO THINK LIKE A PLANT?

Toward a New, Qualitative Science (Part 2)

Stephen L. Talbott

(stevet@netfuture.org)

Perhaps never in the history of the world has so vast a project yielded

such overwhelming benefits at such a terrible cost. The technological

products of our massively institutionalized science are such visible and

effective instruments of power that few would question the essential

rightness of this science as an inquiry into the nature of the world. And

yet, thanks to this same science we find ourselves increasingly alienated

from the world and bereft of any sense of human understanding. What

understanding we are offered derives primarily from instruments and, as

data, passes straight from the instruments to computational machines

fitter than we to cope with it.

The technological benefits of this science hardly need defending. On the

other hand, we find no clarity, no consensus, and in fact precious

little discussion about what it might mean to understand the world. The

crucial notion of scientific or causal explanation is almost nothing but

confusion. My aim in this and subsequent essays will be to clarify some

of this confusion as best I can.

Where Does Unity Reveal Itself?

-------------------------------

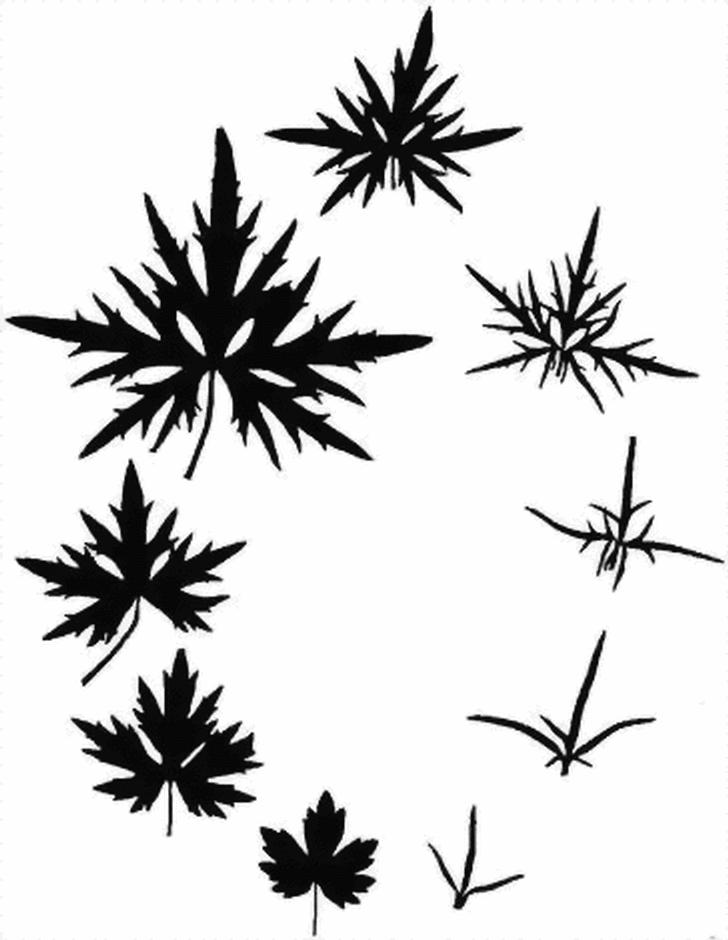

We must start somewhere, so consider the field buttercup (Ranunculus

acris), whose leaves are shown below in Figure 1. Here I will draw

heavily upon a discussion offered by the late philosopher, Ronald Brady

(1987). Brady was a leading expositer of what is often called "Goethean

science" (and what I prefer to call "qualitative science").

|

|

| Figure 1.

Sequence of buttercup leaves.

|

What you see, from lower left, clockwise around the circle to lower right,

is a sequence of leaves taken from a single buttercup plant. The leaf at

lower left appeared first and lowest on the stem, with the others

appearing successively higher in the order shown.

Give yourself time to experience the series repeatedly, moving from one

leaf to the next, both forward and backward. You should do this until you

can, in imagination, provide a smooth series of transitional forms between

any two leaves. Through this process you cannot help experiencing the

entire series as a unity.

But here already we are in trouble if we remain within the frame of

conventional science. The term "unity" suggests some sort of reality

spanning the gaps between material leaves, or hovering over them so as to

constitute the many as one. But what could this reality consist of?

Whatever it consists of, we can say this: the unity that binds material

things or phenomena together cannot itself be just another material thing

or phenomenon.

Unity as a Movement

-------------------

But perhaps, keeping your eyes fixed on the material leaves, you will say

that the unity consists of what the leaves all have in common -- something

we can abstract from the series. Just about the only candidate for this

commonality, however, is a three-part (trifoliate) schema, and such a

schema is compatible with an unlimited variety of radically different leaf

sequences, none of which need be very much like the buttercup. So by

itself the schema hardly gives us a key to the distinctive unity we so

clearly recognize in this particular species. Nor (which is the same

thing) does it elucidate the character of the transformation from one leaf

to the next.

None of this is any surprise. Clearly, what the leaves have in common

cannot by itself enable us to understand the movement from one leaf to a

different leaf. Differences are not a matter of commonality.

Brady suggests that the starting point for understanding must be the

progression itself, not the fixed forms of the individual leaves. In an

initial (and necessarily unsatisfactory) attempt to describe the

progression of the buttercup series in words, we might say that its first

half shows a successive enlargement, or expansion, of the leaf and an

elongation of the separate parts as the leaf becomes more intricately

articulated. In the second half of the series we see a general

contraction along with an ever more severe, and at the same time more

simplified, articulation. But we can already glimpse something of this

later movement in the first half of the series, before it overwhelms the

expansive tendency. And the different aspects we have tried to describe

are in fact caught up within a single, complex-but-seamless gesture that

we can capture only imaginally.

But in representing such a progression imaginally, are we taking hold of a

reality we can work with in any practical way?

Suppose we had viewed the sequence with one of the leaves missing, and

then were given the leaf and told to place it wherever we thought it

belonged. Brady describes the process this way:

The movement we are thinking would, if entirely phenomenal, be entirely

continuous, leaving no gaps. Thus as gaps narrow, the impression of

movement is strengthened, and the technique by which a new form can be

judged consists in placing that form within one of the gaps or at

either end of the series and observing the result. When the movement

is strengthened or made smoother the new form may be left in place.

But if the impression of movement is weakened or interrupted, the new

form must be rejected. Thus the context of movement is itself a

criterion by which we accept or reject new forms.

Read that last sentence again; it is central. The unifying element we

were looking for is nothing other than the movement by which membership in

the series can be determined. This is the element that all the

individual leaves participate in. It is not so much a given thing

they have in common as something they all do, each one entering

into the same, overall gesture in its own place and distinctive way.

A willingness to deal with change or movement as such -- to deal with

movement in its own terms -- is an essential feature of any qualitative

science. And it requires a new kind of thinking. Brady remarks that "the

impression of 'gradual modification' cannot depend any more on what each

form has in common with its neighbors than upon what it does not share

with them. Change demands difference, and continuous change, continuous

difference". That is, we can "see" the movement from one form to the

next only by virtue of a characteristic "distribution of sameness and

difference between them". This dynamic context alone is what brings

out the lawful relation between forms.

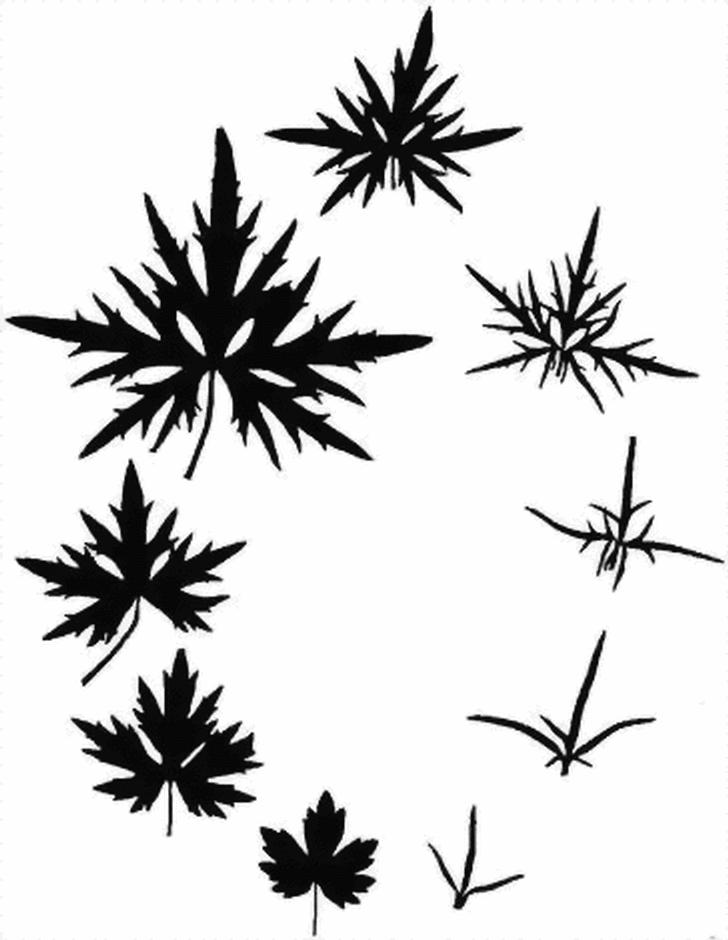

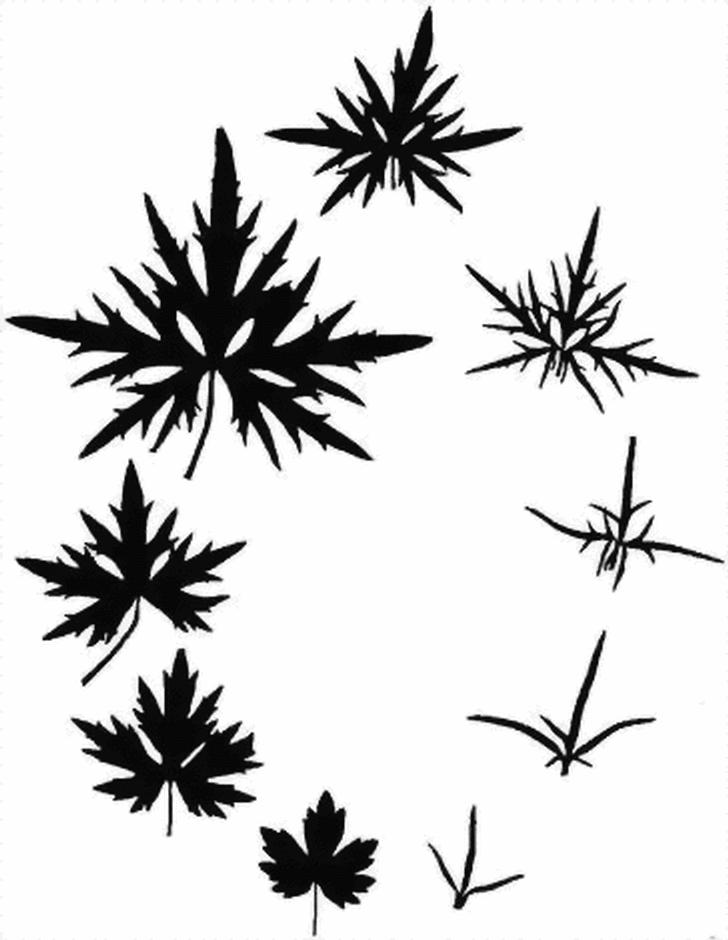

To make the matter more vivid, consider the two leaves shown below.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Two buttercup

leaves. |

If you had seen only these at the beginning, you might well have assumed

they came from entirely different plants. But after you have worked

through the sequence, both forward and backward, bringing it into

continuous movement in your imagination, you can see these two leaves

within the context of that movement, and they will no longer seem unlike.

They will, as Brady remarks, "bear a distinct resemblance to each other,

and bear it so strongly ... that the impression arises that they are

somehow the same form. Here is the intuited 'single form' of the

series, but it cannot be equated with anything static".

The Primacy of Movement

-----------------------

We need to press our consideration of the buttercup just a little further.

As we have seen, no individual form in the leaf series can give us the

difference between forms or the character of the overall transformation.

Brady comments that "The movement is not itself a product of the forms

from which it is detected, but rather [it is] the unity of those forms,

from which unity any form belonging to the series can be generated.

Individual forms are in this sense 'governed' by the movement of the

series in which they are found".

So there are two, very different ways we can think of a leaf in the

series. One is as a given "thing" -- a fixed form considered as an

isolated, static, and material end-product. Seen in this conventional

light, the leaf cannot serve as a revelation of the movement or unity we

have recognized. The isolated leaf, so far as its given form is

concerned, could just as well be part of a different sequence, entirely

unlike the buttercup.

In other words, there is no necessity, implicit in a static end-product,

for a generative movement of a particular sort. The only necessity we

find in our leaf sequence is an expression of the movement itself, which

is capable of generating particular forms out of its own nature. When we

think of the leaf in this second way -- in the context of a transformative

movement with a power to generate particular forms of a particular

imaginal character -- then we no longer have the leaf as a mere thing.

The image of the single leaf, Brady writes, "becomes transparent to the

whole 'gesture' -- which it now seems to express". As we saw when we

looked at just two leaves isolated from the sequence, they can appear

either unrelated or as expressions of a unity, depending on whether we see

them as mere objects or as momentarily frozen gestures of a continuous

movement. In the latter case,

The individual leaf now appears to be "coming from" something as well

as "passing to" something, and by so doing represents to our

mind, more than itself -- it can no longer be separated from its before

and after. Indeed, its only distinction from these moments lies in the

conditions of arrest -- that is, we see it "caught in the act" of

becoming something else .... Each visible form now emerges as

partial, and becomes a disclosure of another sort of form.

Or, as he also puts it, each leaf "is becoming other in order to remain

itself". It has to be becoming other; given that it is in fact a

manifestation of a movement, it can retain its identity only so far as it

is itself seen to be in movement. Every leaf is now representative of all

the others in the series because each is born of the same movement. This

is how the two forms of Figure 2 manage to look alike.

This means that the difference between two leaf-forms is required if we

are to see the kind of unity at issue here. If in Figure 2 we had two

identical forms, we would be able to say nothing about any unity or

generative movement. Mere sameness is not unity, and it cannot give us

movement. This is why a science based on abstraction, whereby we abstract

from things their sameness -- what they have in common -- cannot deal with

the various sorts of dynamic unity we find in the world's phenomena.

Finally, pattern and Gestalt have become popular terms today in some

branches of science, but we need to distinguish these terms, as they

are general employed, from the "movement" or "gesture" we have been

considering here. Goethe summarizes the matter this way:

The German has the word Gestalt for the complex of existence of an

actual being. He abstracts, with this expression, from the moving, and

assumes a congruous whole to be determined, completed, and fixed in its

character.

But if we consider Gestalts generally, especially organic ones, we

find that independence, rest, or termination nowhere appear, but

everything fluctuates rather in continuous motion. Our speech is

therefore accustomed to use the word Bildung pertaining to both what

has been brought forth and the process of bringing-forth.

If we would introduce a morphology, we ought not to speak of the

Gestalt, or if we do use the word, should think thereby only of an

abstraction -- a notion of something held fast in experience but for an

instant. (Quoted in Brady 1987, p. 274)

What has been formed is immediately transformed again, and if we would

succeed, to some degree, to a living view of Nature, we must attempt to

remain as active and as plastic as the example she sets for us.

The Explanatory Power of the Whole

----------------------------------

All this lands us in territory both familiar and strange to science.

Everyone, with some inner, imaginative work, can recognize the coherent

movement, or shaping potential, that engenders and unifies the leaf

sequence. This is hardly esoteric stuff. But what sort of reality can

be claimed for a movement or shaping potential we can recognize only

between material leaf forms, and what do we mean when we say the

movement governs the individual forms? Can we say in any legitimate

sense that the movement accounts for or explains the forms -- or that it

brings us scientific understanding of the buttercup?

To say any of this is to appeal to principles of understanding and

explanation that stand behind or precede the phenomenal appearances they

apply to. Brady is indeed invoking such principles when he speaks of "a

law by which the plant produces its multiplicity of forms", and also of a

"whole which designs its own parts". Contrary to our analytic habits, he

says, we must learn to think from the whole to the parts. However, so far

as we remain stuck in those usual habits, we can scarcely imagine the kind

of immaterial unity at issue, and therefore we may object to the

"obscurity" of all references to it.

The objection rings hollow. There is nothing particularly obscure about

the structure of our cognitive activity in grasping the unity of the

buttercup, as outlined above. We "see" this unity beyond any doubting,

and it is dangerous to the health of science when we ignore what is right

in front of us. Moreover, we have already noted (Talbott 2005) that the

recognition of such unity is a routine, if underappreciated, experience of

the scientist. For example, every biologist and every naturalist relies

upon this irreducibly qualitative experience when identifying and

classifying species.

Such recognition of unities that cannot be equated with any particular

collection of physical things must be acknowledged by anyone who is not

already shut off from the testimony of his own senses. A qualitative

science does not posit some mystical and unknown source of insight. It

simply refuses to ignore the routine powers of cognition prerequisite to

all scientific analysis. After all, we cannot meaningfully analyze and

divide unless we are first given a significant unity to analyze. If there

is obscurantism here, it lies in the refusal to take a critical,

investigative stance toward the starting place for all our scientific

work. It lies in the willingness to build this work upon a kind of

cognitive blank.

If we prefer to fill in this blank, we need to reckon with, among other

things, the explanatory power of the dynamic unity observed in the leaf

series. In a sense, the matter is so simple as to preclude argument. We

see an overall gesture in the temporal unfolding of leaves on a plant.

This gesture cannot be equated to any tangible object, and it clearly

gives us a much fuller picture of the reality of the plant than any

collection of tangible objects alone could possibly give us. The gesture

expresses something of the character and unity of the plant that we can

grasp no other way. It gives us the life and the becoming of the plant

rather than isolated, frozen snapshots taken from that life. Do we really

need to debate which approach captures more of the world's reality -- the

snapshot or the underlying gesture that engenders and lives in all such

snapshots?

The problem is that we have carried over from the nineteenth century an

outmoded desire for explanation in terms of the impact of particle upon

particle, gear upon gear, object upon object. More recently, as we saw in

"The Vanishing World-Machine" (Talbott 2003), explanation has shifted

toward the formalisms of logic, rule, equation, and algorithm. These two

modes of explanation have tended to combine, so that we feel most securely

possessed of understanding when we can picture machine-like objects whose

"gears" and "levers" seem to be little more than condensations of logic --

when, in other words, we can picture the world in the way we picture a

computer.

By comparison, the unity we observe in the leaves of the buttercup may

suffer from all the vagueness and insubstantiality we associate with

consciousness. It seems to be a a mere image held in our minds. It is

more pictorial and imaginative than logical and computational. It does

not readily lend itself to the action of gears or levers or transistors.

To equate it with any particular physical object is, in fact, to lose it.

Can such a pictorial idea manifesting in our consciousness contribute to a

genuine understanding of the world?

But, crucially, the idea does not manifest only in our consciousness.

After all, we recognized it in a series of leaves. It is the kind of idea

botanists routinely encounter in the phenomena they deal with, and is

required in order to make these phenomena intelligible. Where is the idea

if not in the phenomena that demand it from any understanding mind?

Many scientists, of course, will stumble over the notion that what occurs

to us as imaginative idea may occur in the world as well, where it acts as

a kind of shaping power. "How", they will ask, "does a mere idea gain

power to mold the physical world?"

Actually, our science of laws and causes points us toward nothing but such

shaping power. I certainly do not wish to equate the lawfulness of

gravity with the lawfulness of leaf transformation; they are very

different sorts of lawfulness. But if the governing unity of the leaf

series is not a physical thing, neither are the equations we identify with

the law of gravity. The principles of order in both cases are neither

more nor less than articulations of our conscious activity.

But the whole point of articulating these principles in our minds is to

elucidate the phenomena we encounter. These principles either do or do

not make the phenomena intelligible, and if they do, then they undeniably

belong to the phenomena. And they cannot belong to the phenomena while

residing solely in our heads.

Yes, the notion that imaginative contents have a power to shape the world

is alien to modern sensibilities. But to find ourselves continually

forced to draw, not only upon mathematics, but also upon dynamic images

in our attempt to understand the world, and then to deny that, not only a

mathematical shaping power, but also an imaginal shaping power is what we

see at work in the world -- this requires a human being who is at war with

himself. The only thing I know of that could drive one into this

self-contradiction is the materialist's urgent need to avoid recognizing

anything of an inner, living character in the objective world around us.

But you cannot really even have gravity except as (among other things) an

imaginal power. It manifests itself in the characteristic forms of

physical movement -- as when you throw a ball -- but makes use of no gears

or transistors in playing its role. If you stop and think about it, you

will find you have no more reason to ascribe explanatory power to the

physicist's formulation of the gravitational law than to the governing

gesture of the buttercup. This remains true despite the drastically

different kinds of form evident in the two cases.

Intelligibility Comes from Within

---------------------------------

A great deal needs to be said to enflesh these brief suggestions. For the

moment I will conclude my comments with the barest sketch of some of the

territory we will need to survey more fully, especially when we come to

the epistemological underpinnings of a qualitative science.

What conventional science has done with the law of gravity is to make

it so thin and abstract, so bloodless, so empty of content, that we can

easily forget its true nature. But, however much we have emptied them of

all but quantitative content, our gravitational equations remain nothing

if not expressions of our mentality. Numbers and formal relations

are not physical things. Ironically, the materialist who more and

more sees the world in terms of equation, rule, and algorithm -- and

who, like the philosopher Daniel Dennett, can say, for example, that

evolution just is an algorithm -- has become a kind of airy idealist.

His "physical" world is almost nothing but mentality -- and mentality of

the most insubstantial sort.

But whether you consider this science of abstraction to be materialism or

idealism, it remains largely vacuous for the simple reason that high

abstractions have almost no content. I said a moment ago that we have no

more reason to ascribe explanatory power to the usual formulation of the

law of gravity than to the governing gesture of the buttercup. Actually,

we have less reason to consider the gravitational law, in its usual

formulation, explanatory. The problem is that we have no meaningful law

of gravity so long as we take Newton's (or any later) equation in its

strictly abstract and quantitative aspect. We have to have qualitative

concepts of mass and force as well. Without these concepts, we might see

objects moving along certain mathematically describable trajectories, but

we would have no sense at all that each object was attracting or pulling

the other.

Where do we get a concept of force? You will struggle in vain to find any

origin for it other than in your own inner experience -- for example, the

experience of exerting your will to move your muscles, and the experience

of being drawn or compelled by the force of someone's personality. In

such experience we find the prerequisites for our scientific thoughts

about force even if we tend to ignore the experience while working with

our equations. If Eddington had reckoned with this source of our

scientific insight and had been able to integrate it into his science, he

would not have had to say, as we heard in "Do Physical Laws Make Things

Happen?" (Talbott 2004):

[Our knowledge of physics] is only an empty shell -- a form of symbols.

It is knowledge of structural form, and not knowledge of content. All

through the physical world runs that unknown content.... (1920, p.

200)

The only way to gain the unknown content is to cease neglecting the only

content we are given, which is the inner content of our own experience.

This experience is the primal source of any science, any knowledge of the

world, we could possibly have. Eddington could find only empty structure

because his science refused to acknowledge its reliance upon human

experience or to recognize the human being as by far the most perfect

"instrument" for perceiving the world -- the only one of our instruments

capable of supplying the content from which all data is abstracted.

Returning the data to its original, qualitative context is, obviously

enough, the only way it can become meaningful. And wrenching the data

away from its context is, obviously enough, a formula for denaturing the

world, and for reconstructing it in the image of a badly compromised human

instrument -- compromised because abandoned from the neck down, leaving

only our ability to emulate a computer.

Our choice, then, is not between remaining respectable, hard-headed

materialists or else projecting fanciful, immaterial ideas upon the

physical world. Rather, it is between projecting a drastically

inadequate, anemic, abstract mentality upon the world (while forgetting

that this is nevertheless a content of our own consciousness), or else

discovering in ourselves the imaginative, muscular, aesthetically felt

contents that can render the world more fully intelligible.

Why should we employ less than our full range of our conscious awarenesses

when we try consciously to understand the world? Where does the world

impose upon us the rule, "ignore everything but your capacity for

measurement when you contemplate nature"? How can we forget that

measurements mean nothing except so far as we know what we are measuring?

And there is no what given except the quality. (Go ahead: try to

describe any what you wish without resorting to qualities.)

We have seen with the buttercup a little bit of what it means to apprehend

the qualities of things. A certain quality of the buttercup (we could

also say: a certain meaning of the buttercup) is expressed in the

gesturing of its leaves. To capture this gesturing we had to do inner

work, bringing the gesture to life within ourselves. Our imagination had

to be brought willfully into movement.

This effort of will, as a conscious work, is what we usually lack when

thinking much too easily about gravity -- that is, when manipulating

well-defined equations while forgetting that these equations are about a

power of movement. We can scarcely hope to understand this without our

own experience of the power of movement. The problem with science today

is that it stops short of knowing the physical world -- as opposed to the

self-contained domain of logic and mathematics -- because it ignores the

many-faceted inner realm where we experience the world as much more than

measure and quantity.

Ideas or laws in the qualitative, imaginal sense I have been speaking of

are nothing other than the phenomena themselves in their transparency to

understanding, in their expressiveness, in their different ways of being.

Expressing this or that character is what physical phenomena do. It is

what gives them content. It is the life by which they exist. Phenomena

would be nothing to us if they were not intelligible expressions. In some

ways the last few hundred years of science have amounted to the insane

project of mapping reality according to a schema of intelligibility while

denying intelligibility to reality.

Within human consciousness we discover a language for understanding the

world (Rozentuller and Talbott 2005). If this were not so, we could only

stare blankly at our surroundings. What scientists need to realize is

that our conscious (and unconscious) interior is vastly richer than the

contentless abstractions playing over the convoluted surface of our

brains. We are creatures of imagination, of heart-felt feeling, and of

will raying out through our muscles and bones. And to the degree we must

call on the full powers of this inner language in order to comprehend,

for example, the leaves successively gestured forth along the stem of a

buttercup -- to the degree this language makes the world intelligible --

we must acknowledge that the language speaks truly. That is, it reveals

the world, which is to say that what speaks in us speaks also in the

world.

Or, as the ancients might have put it: the same logos shines through both

the world and the human being. How could it be otherwise?

Much more remains to be said.

Bibliography

------------

Brady, Ronald H. (1987). "Form and Cause in Goethe's Morphology", in

Goethe and the Sciences: A Reappraisal, edited by Frederick Amrine,

Francis J. Zucker, and Harvey Wheeler, vol. 97 of Boston Studies in the

Philosophy of Science, edited by Robert S. Cohen and Marx W. Wartofsky.

Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co., pp. 257-300.

Eddington, Sir Arthur (1920). Space, Time, and Gravitation. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Rozentuller, Vladislav and Stephen L. Talbott (2005). "From Two Cultures to

One: On the Relation Between Science and Art", In Context #13. Available

at: http://natureinstitute.org/pub/ic/ic13/oneculture.htm.

Talbott, Stephen L. (2005). "Recognizing Reality", available at

http://natureinstitute.org/txt/st/mqual/ch08.htm. Originally published

in NetFuture #162 (April 5, 2005).

Talbott, Stephen L. (2004). "Do Physical Laws Make Things Happen?", available

at http://natureinstitute.org/txt/st/mqual/ch03.htm. Originally published in

NetFuture #155 (March 16, 2004).

Talbott, Stephen L. (2003). "The Vanishing World-Machine", available at

http://natureinstitute.org/txt/st/mqual/ch01.htm. Originally published in

NetFuture #151 (October 30, 2003).

Goto table of contents

==========================================================================

ABOUT THIS NEWSLETTER

Copyright 2005 by The Nature Institute. You may redistribute this

newsletter for noncommercial purposes. You may also redistribute

individual articles in their entirety, provided the NetFuture url and this

paragraph are attached.

NetFuture is supported by freely given reader contributions, and could not

survive without them. For details and special offers, see

http://netfuture.org/support.html .

Current and past issues of NetFuture are available on the Web:

http://netfuture.org/

To subscribe or unsubscribe to NetFuture:

http://netfuture.org/subscribe.html.

This issue of NetFuture: http://netfuture.org/2005/Jul0505_164.html.

Steve Talbott :: NetFuture #164 :: July 5, 2005

Goto table of contents

Goto NetFuture main page